Liberia 2012: Anna's Story

In 2012. I spent a week in Liberia with Save the Children. At the time I wrote two stories from my experience. Since then, the country was hit by Ebola and sadly, the situation is not much better today.

I walked into theatre. A girl was lying flat out on the operating table, her eyes fixated on the ceiling. I wasn’t certain if she was still alive, there were no monitors beeping, in fact there were no monitors all together. The theatre looked like a battlefield, blood was everywhere, soaking the drapes, trickling onto the floor to join the heap of soaked swabs. Her abdomen, splayed open as the surgeon was fighting to save her life after her womb has ruptured during labour. I saw her take a breath. It suddenly dawned on me: she was awake.

Anna was twenty years old and this was her second pregnancy. What was happening was quite predictable after her last pregnancy. During her first labour the baby’s head would not pass through her pelvis and became obstructed. After two days in labour she managed to get transferred to the hospital to have a Caesarean section delivering a live baby. But the damage was already done. Whilst her baby’s head was stuck, it cut off the blood supply between her bladder and vagina, resulting in an obstetric fistula. This meant that the she no longer had control of urination, becoming incontinent. Were it not for the repair carried out by an international charity she would have been ostracised by her family and village because of constant wet and offensive smell.

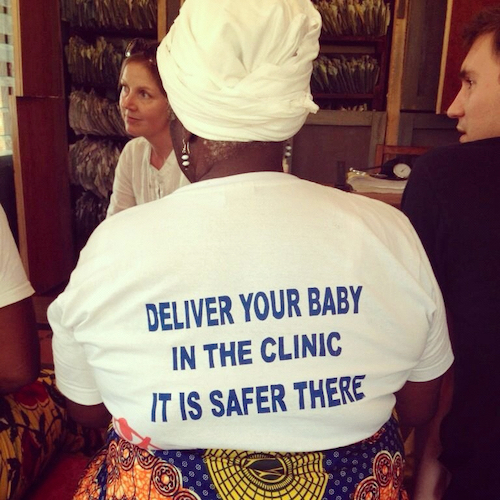

The scar on her womb from the previous Caesarean section and surgery is a weak area. Despite warnings she attempted this second birth in her village. There could be many reasons for this; she had too little money to pay for transport, had another child to care for and had been reassured by the untrained traditional birth attendant who was reliant on her home birth for her survival. Once again her labour was obstructed. Eventually the scar could take no more and ruptured.

Now she was fighting for her life. After her womb had ruptured the baby was born into her abdomen. It couldn’t survive and sadly died before she got to hospital. Struggling with unimaginable internal bleeding, she needed a highly skilled team to give her the best chance of survival. This rarely happens in the UK, because all women with a previous Caesarean section are advised to give birth in hospital and their labour is carefully monitored. If it does it is a major emergency involving an array of senior doctors, obstetricians, experts in blood transfusion and anaesthetists to rush her to theatre and put her to sleep for major surgery.

She had an epidural-like anaesthetic and a student nurse, still learning basic medicine, was injecting something into her arm. I asked what it was. Ketamine, horse tranquilliser. I’d be pretty concerned if I saw this in the UK, but it actually made a lot of sense. There was only limited equipment to monitor her blood pressure and nothing to control her breathing, not to mention the shortage of skills and experience and ketamine is much safer in these circumstances.

Anna’s pulse was racing fast as her heart pumped to get oxygen around her body. Along with the massive amount spilled on the floor, some results were back from the lab showing that she needed a blood transfusion. Calling the blood bank wasn’t an option as there wasn’t one. Blood needed to be donated by family members, which is commonplace in Africa. I was hoping someone outside was arranging this quickly.

This really is a griping story of life and death. At first glance I was horrified by it all. Horrified by the fact that Anna got into this situation in the first place, the short supply of well-trained health professionals, the basic equipment available and the limited availability of blood products. Overall I thought it was substandard care that would be considered negligent at home. But then I could see the courage, determination and compassion shown by the team. With what they had available they were doing their best. Without their commitment and struggle Anna would die for certain. They gave her their all.

Once everything was under control the surgeon handed over to his assistant to close up. I asked him what he thought her chances of living were. He humbly replied “we don’t have much but we do our best”.

Stories like this are unfortunately commonplace in Liberia. Women have a 1 in 24 chance of death during childbirth, most women die from excessive bleeding. However things are beginning to change, structures are being put in place to prevent and deal with emergencies and health care facilities are well supplied. I will talk more about how things are improving, but how the situation if fragile in future posts. For now I think we need to reflect on how fortunate we are in the UK and to support the work of charities like Save the Children and continue to fight the case for international aid.

August 24, 2020 | @DrMattPrior