I see many patients who are concerned about lighter periods or short cycles. A short luteal phase has long been attributed as a cause of infertility and miscarriage. Here is a summary of the research looking at how a luteal phase defect may influence fertility.

What is the luteal phase

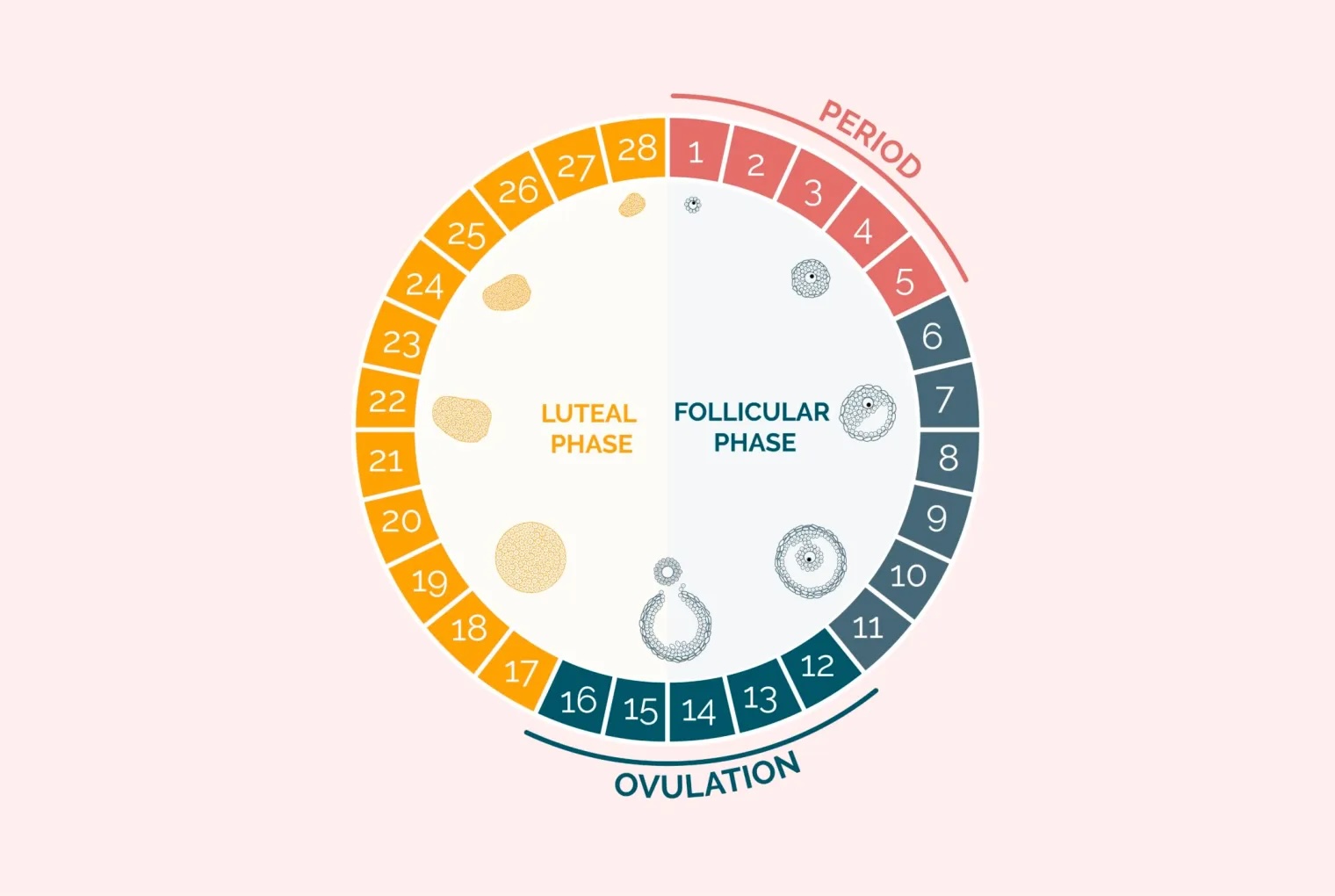

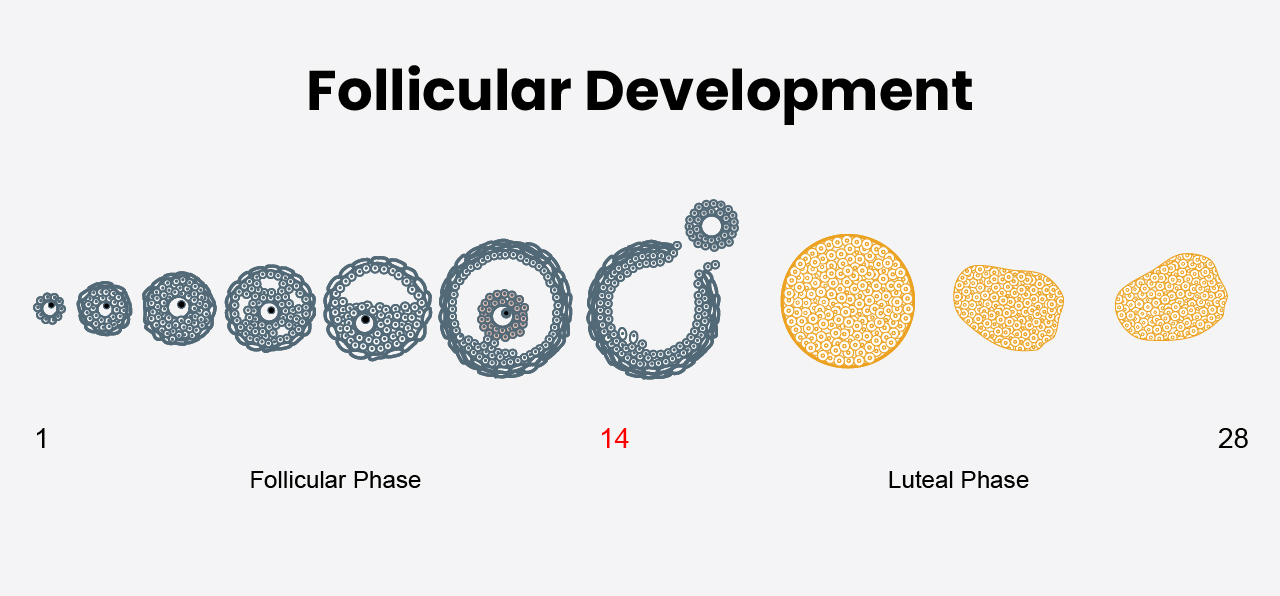

The menstrual cycle can be divided in two. During the first part of the cycle, the follicular phase, the ovary develops eggs inside follicles which begin to grow. After several days one follicle grows larger than the others. This dominant follicle then goes on to release an egg at ovulation.

The dominant follicle’s job does not finish with ovulation. Now called a corpus luteum, the follicle produces progesterone for the rest of the cycle. Hence the second half of the cycle is known as the luteal phase.

If you look in a textbook, each half of the cycle is an equal 14 days in length resulting in a 28 day cycle. However, women aren’t like textbooks. Cycles can vary in length and studies looking at when ovulation occurs show that this can also vary from cycle to cycle, even in women with regular periods.

Progesterone

Progesterone is the hormone responsible for maintaining the lining of the womb and is essential for pregnancy. The name itself literally means ‘pregnancy hormone’, derived from Latin: pro- (‘for’), gestare (‘to carry’ or ‘to be pregnant’), and -one (as in hormone). Therefore, it’s logical to think that fertility problems or early pregnancy loss are due to a deficiency in progesterone. In fact, the first scientific reference to a “luteal phase defect” was published in 1949.

So far, the story sounds good, but digging a little deeper things start to fall apart. Science and medicine need more than just a good theory and should be backed up with research based evidence.

How do you define luteal phase defect?

Clear definitions are essential for comparing results across studies and ensuring consistency in clinical research. However, varying definitions of a “short luteal phase” have led to confusion about which patients are truly affected. Different doctors and researchers use slightly different definitions. Some say the luteal phase is short if it lasts 8 days or less, while others use 9, 10, or even 11 days as the cut-off. Some definitions are based on hormone levels, especially progesterone, instead of just the number of days. Because of these differences, it can sometimes be hard to say exactly who has a luteal phase defect. These inconsistencies highlight the need for a standardised definition to facilitate accurate diagnosis and meaningful comparisons across studies.

What causes a short luteal phase?

Given that the definition is vague, trying to explain why some women have a short luteal phase is difficult. Proposed explanations include problems with the first part of the cycle, the follicular phase, or abnormal hormone control of the menstrual cycle from the brain. Disorders of thyroid and prolactin have also been implicated along with kidney problems, breast-feeding, obesity and age.

Perhaps the most important association is that a short luteal phase may occur in healthy young women.

- Dr Matt Prior

Diagnosis

Tracking the exact time of ovulation is notoriously difficult. Different methods for diagnosing a short luteal phase are all based on identifying when ovulation occurred. The table summarises some of these methods and their pros and cons.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Tracking basal body temperature (BBT) | Just need a thermometer | – inaccurate – inconvenient |

| Urinary ovulation predictor kits that detect the LH surge | Easy to perform and readily available | – not always accurate – can cause anxiety – a short luteal phase may occur in healthy women – a false-positive LH surge is found when testing urine in >7% of cycles in women with regular menstrual cycles. |

| Progesterone blood levels | Provides evidence of ovulation, but not when | – Progesterone is secreted in pulses and levels can vary up to 8 times in 90 minutes. – Unfortunately, there is no recognised pattern of progesterone levels during the luteal phase in normal fertile women. – No minimum progesterone level defines “fertile” luteal function. |

Problems with progesterone measurement

The corpus luteum varies from cycle to cycle in normal fertile women. Therefore, random serum progesterone levels are not valid between cycles. Furthermore, progesterone levels can fluctuate throughout the day. The highest level can be as much as 12 times higher than the lowest level, so a “low” progesterone doesn’t necessarily reflect the true picture.

Once pregnancy has been established the corpus luteum is stimulated by the pregnancy hormone, hCG, to produce progesterone. Progesterone levels have some value in predicting if the pregnancy is nonviable or extrauterine, but again this is limited.

Low progesterone levels in early pregnancy are likely to reflect abnormal hCG stimulation of the corpus luteum by a nonviable or extrauterine pregnancy rather than a problem with the corpus luteum. A low progesterone level obtained at the time of, or after, diagnosis of early pregnancy should not be used to start progesterone treatment.

Is luteal phase defect associated with infertility and pregnancy loss?

Ultimately, the main aim of trying to conceive is getting pregnant. I can understand the appeal of the concept of a short luteal phase to explain why pregnancy is not happening. Nevertheless, when comparing women with a short luteal phase to those who do not, the rate of infertility at a year is not significantly higher.

Although an isolated cycle with a short luteal phase may negatively affect short-term fertility, incidence of infertility at 12 months was not significantly higher among these women.

Does treatment for a luteal phase defect improve reproductive outcomes?

Given that the definition of luteal phase defect is variable and results from studies include both fertile and infertile women, the research looking at potential treatments is not very good quality.

If a woman has another underlying problem such as hypothalamic amenorrhoea, high prolactin or obesity, these problems should be treated. Nevertheless, beyond that the only potential treatment is progesterone supplementation.

Progesterone can be given as tablets, injections or pessaries. Commonly, progesterone is used as part of assisted conception treatments when the natural cycle has been modified with drugs which impair progesterone production.

Currently, there is no evidence that progesterone supplementation provides any benefit for women having natural cycles. No randomised-controlled trials have been done to investigate progesterone supplementation for women with a luteal phase defect.

Take home messages

- A luteal phase defect has no clear definition and has not been proven to cause infertility or pregnancy loss.

- A short luteal phase can be found in normal healthy women.

- Women with a “short luteal phase” have the same pregnancy outcomes over a year compared with those with “normal” cycles.

Sources

- Jones G. Some newer aspects of the management of infertility. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1949.

- Strott T. The short luteal phase. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1970.

- McGovern P. Absence of secretory endometrium after false-positive home urine luteinizing hormone testing. Fertility and Sterility. 2004.

- Filicori M. Neuroendocrine regulation of the corpus luteum in the human. Evidence for pulsatile progesterone secretion. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1984.

- ASRM. Current clinical irrelevance of luteal phase deficiency: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility. 2015.

- Crawford N. Prospective evaluation of luteal phase length and natural fertility. Fertility and Sterility. 2017.